The definition of Somma is simple: it is the experience of feeling one’s body without paying attention to it. Somma is what persists in your conscious impression when you strive to clear your mind, are not focused on anything physical or abstract, inside or outside. You have not ceased to exist. You are your Somma.

Sommaire

- 1 But it already exists!

- 2 Between map and representation

- 3 Why this neologism?

- 4 Cenesthesia

- 5 Ranks of sensation for Schiff

- 6 Melancholy of cenesthetic origin

- 7 Regression to body schema

- 8 Somma is not in place at birth

- 9 Psychoanalytic reclamation

- 10 Do not put the image before the body

- 11 History of the child or the rejuvenated adult?

- 12 Ontology in physical technicality

- 13 Small defects of somatics

- 14 Physically push the Somma and tow it into the abstract

But it already exists!

Why not just talk about the presence of the body? When I say “I feel my body,” isn’t it the same thing?

Not quite. Your answer includes “I” and “my body.” It’s an interaction. By deconcentrating, you stop being this or that in “I.” Nothing is there to “feel” the body anymore. But it is nevertheless present.

Isn’t this what neurologists call the body schema, this mapping established by the sensory and motor areas?

The body schema is indeed the source of Somma but it is neutral. It spatializes the sensations, does not interpret them any more. Your Somma is not just a map. It is a surprisingly rich phenomenon, paradoxically fusional and pointillist. The impression is one, but within this unit you feel protrusions, regions more alert than others.

Illustrations:

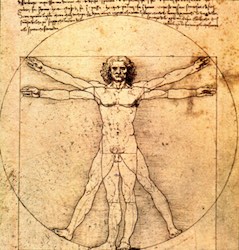

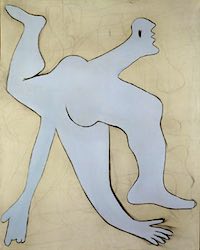

Vitruvian Man: the ideal body by (the consciousness of) Leonardo da Vinci

Body schema: the body spatialized according to the richness of its sensory afferents

Somma: the experience of the body with Picasso, halfway between the previous ones

Between map and representation

Somma is not always a pleasant phenomenon. It can include annoying places, even torture poles, or be overall unpleasant (fibromyalgia). This feature takes it a lot away from a simple schema. The map is heavily annotated. Layers of sensory cues. Functional areas, sensitive areas to protect. Aerial photographs and aesthetic notes… By stacking all levels of meaning, we arrive at the psychologically complete body image.

Between the anatomical map and the conscious self-image stands the Somma. Nor reduced to a body in space, because we feel that the ship is inhabited. Nor a film actor, because ideals fade if consciousness does not summon them. The phenomenon remains. A first-person experience, one of the most real. This is Somma.

Why this neologism?

Where does this neologism close to ‘soma’ come from and why was I forced to use it? The notion seems simple and has been widely discussed. Yet it remains unclear. For its misfortune it is located in the middle of the body/mind gap, which is always crossed only by fragile bridges. No official theory of mind has filled it. Let’s visit, if you are interested, the history of the integration of the body and its image.

“Body image in neurology and psychoanalysis: History and new developments (2003)”, by Catherine Morin and Stéphane Thibierge, is a complete and absolutely remarkable article on the subject. A rehabilitator and specialist in the human sciences, this is the perfect ontological/epistemological duo to analyze what is at the confluence of the two approaches. I will take up the essential points of their work and comment on them if necessary.

Cenesthesia

The oldest concept of body image is cenesthesia defined by Hübner in 1794: “general sensitivity that represents to the soul the state of its body”. He differentiates it from “sensitivity that informs about the external world”, and from “internal sense that gives representations, judgments, ideas and concepts”.

This systematization of Hübner is still surprisingly right. Intrinsic and extrinsic sensitivity are effectively treated independently to form the image of oneself and the world, the treatment center being the ‘internal sense’ or proprietary mind.

Ranks of sensation for Schiff

In 1873, Schiff explained how cenesthesia was formed: “If, for example, irradiation (from excitation to the centers) goes to a sensory center, it will awaken the image of a color of a sound, of an object; an auditory impression can thus produce a visual sensation or an auditory impression or both at the same time; such a secondary sensation will in turn produce a tertiary one and so on. In this way a single sensation can awaken an infinite chain of central sensations of sensory images and as all our thought moves in such images or more exactly is nothing other than a series of central images, that is, excitation of the central termination of the sensory nerves, it follows that a sensation can produce a series of thoughts that, combined with primitive sensations, must complement or rather constitute cenesthesia”.

Seeing the sequence of thoughts as a result of the interaction of sensory endings and the world is too behaviorist, but the idea of hierarchical sensations to thought is avant-garde. Schiff tries to cross the body/mind divide through ontological direction.

Melancholy of cenesthetic origin

In 1895, Séglas believed that the cenesthetic disorders responsible for melancholy: “As a result of the disorders that occur in the field of organic functions at the beginning of melancholy, the normal cenesthetic state, of well-being, produced by the harmonic consensus of organic sensations gives way, once the balance is broken, to a new painful cenesthetic state of general malaise […] the first cause of moral pain.”

Perhaps contemporary doctors, who don’t understand anything about fibromyalgia, should re-read Seglas. The “painful cenesthetic state” is indeed a perfect description of the disease.

Regression to body schema

In 1902, Bonnier criticized cenesthesia for its lack of “topographical figuration indispensable to any definition of corporality.” He brings the image of the body back to its spatial form, with the notion of schema.

In my opinion, this is a mistake, which strips the image of the body rather than it specifies it. It refers this image to the simple sensitivo-motor spatialization, to a postural function. This function is certainly important, but it represents only part of the more complete notion of cenesthesia. A quadriplegic, having lost his body schema, would no longer have a body image with the reduction operated by Bonnier. But yes, it disposes of it, thanks to the intrinsic sensitivity preserved. The internal organs participate in our cenesthesia, but we cannot say where they are located. Only the contraction of the smooth muscles with which some are associated makes them appear in the schema.

Somma is not in place at birth

In 1931, Wallon showed how the notion of the own body develops in children. “The body is first treated by the child as if it were made of distinct parts, each animated by a personal life: such a child can thus offer pieces of cake to his toes. Between six months and two years, the child discovers his image in the mirror and, unlike the young chimpanzee, he takes a prolonged interest in it, even after noticing its fictitious character: he gloats in front of his image. He turns to the adult, begging for his assent to this image that is his.”

Does “the child identify with the shape of his body even though his body schema is not constituted”? No, Wallon is wrong. The child sees his twin. That’s why he can play with him, and with the parts of his body. The body schema is there but is not assembled. Missing the Somma. Child psychology is too young to have created it.

Psychoanalytic reclamation

In 1935, Schilder, both neurologist and psychoanalyst, replaced the body schema with the term ‘body image’. In fact he goes back this notion higher in psychology by basing it on 3 components, physiology (classical neurological scheme), Freudian libidinal structure (erogenous orifices), and the sociology of body image.

In 1949, Lacan charged even more the image of the body with symbolic meaning, with “The stage of the mirror as a formator of the function of the I as it is revealed to us in the psychoanalytic experience”. For him, the mirror phase, in the child, passes the image of the fragmented body to that of a single visual image, identity, with a proper name and sexuality. It is to this fusion that psychoanalysis gives the name of specular image.

The flaw of psychoanalysis is to want at all costs to inscribe an adult teleology on a very simple neurological self-organization in reality. A caricature of this process was Freud’s inscription of the Oedipus complex in the fundamental determinants of psychic structure. Lacan falls into the same ruts. He is looking for how little Lacan was built and not the image of the body. Little Lacan did not build himself as ordinarily as neurologists claim. You have to bring a little salt to this story.

Do not put the image before the body

The fusion of body pattern, erogenous zones, and social body image, is an ontological process. This is already what Schiff was saying with his primary, secondary, tertiary impressions, etc. No need to put an intention at the end to achieve the merger. One wonders how it would pre-exist there. There is also no need to put mandatory experiences on the path. Would a child who never crosses a mirror be unable to unify his symbolic identity?

The only interest of the concept of ‘specular image’ is that there is ultimately a conscious personality who examines his own body image. It is in adults that the concept takes consistency. The secular image is the aspect of somma seen by the downward, teleological look.

History of the child or the rejuvenated adult?

The aspect of Somma seen through the upward, ontological look does not really appear in the work of Catherine Morin and Stéphane Thibierge. In fact, the story in the child is told by the adult. The defined image of the body is that of the level at which the authors wanted to situate it, between bodily schema and identity “I”, according to their school of thought.

But the image of the body makes fun of schools of thought, neurological patterns and psychoanalytic chapels. It is a dynamic image, which moves on the scale of mental complexity, at every moment of our life, according to mood, stress, physical accidents, metaphysical journeys. If a horse crushes your hoof foot, your body image is concentrated entirely there, and for a few hours. If you are placed in a sensory isolation box and do not think of anything specific, the body image is the presence of your internal organs, devoid of location, hence this strange impression of dispersion. Writing this article, my body bothers me because it wants to move, does not support a frozen posture. I try to focus entirely on concepts and physical sensations do not help me. My Somma is no longer corporeal actually.

Ontology in physical technicality

Where do we find the most relevant ontological views on body image? In those who repeat and refine their physical activity. They have an extraordinarily developed body schema. Much more than neurologists, philosophers and psychoanalysts. But they talk about it less well. Are better for techniques than for theories. Willingly move from technique to esoteric interpretation, without an intermediate station. They thus lack recognition from more academic disciplines.

The precursors of this lived ontology of the body are the movements of physical culture born in the nineteenth century. They interfaced themselves in the twentieth century with dance, choreography, existentialism, oriental gymnastics, to give birth to a multitude of techniques and schools of development and physical rehabilitation. Thomas Hanna created in 1976 the term ‘somatics‘ to designate this integration body / mind through physical stimulation.

With this look we also return to Seglas’ conception of psychological disorders of cenesthetic origin, or Karen Horney’s definition of neurosis: the body does the opposite of what we think. The objective image is not in line with the image experienced.

Small defects of somatics

This incorporation (mind/body integration) is called ‘soma’ by Hanna and the Somaticians. We arrive on my Somma by the upward, ontological look. The two notions coincide and the somatician approach is more flexible and pragmatic than the specular image of psychoanalysts. I wanted to create a different neologism for 2 reasons:

1) ‘Soma’ already has two alternative meanings in biology: ‘body of the neuron’, and ‘set of non-sexual cells of the organism’. Adding a third, semi-biological, creates confusion.

2) Somatics is the subject of many esoteric reclamations, that is to say that the upward look starts from physical techniques but does not stop at soma. It continues to the soul and mystical global consciousnesses. As much as the specular image lacks physical anchoring, somatic is lost in the conscious imagination.

Physically push the Somma and tow it into the abstract

For a person to find or rectify her Somma, the two looks must meet. By using the psychoanalytic look in isolation, she makes Somma an abstraction and rejects it without being able to grasp it. She gloats endlessly on it but nothing changes physically. Using the somatician look in isolation, she does the opposite: her physique changes but she loads her personality with stereotypical esoteric concepts.

If you have understood the notion of Somma and its dynamic character, you can alternately make room for consciousness, through readings and biographical introspection, and body development, through the practice of gymnastics. You thus firmly connect the two looks on your Somma. This solidly established link is the heart of your insurance. It is then easy to extend your conscious and physical originalities to both ends of mental complexity.

*